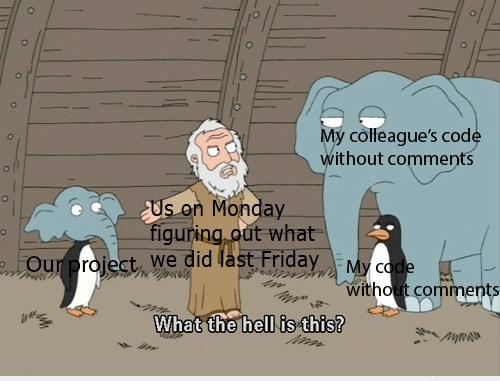

I frequent a popular forum dedicated to making jokes about programming. The jokes shared are usually inoffensive–many are downright relatable–but periodically I’ll find one that gets under my skin. Today it was this one:

I’ve noticed that jokes like this on the forum tend to get a lot of traction and a lot of supportive comments, while comments that express opposition to this sentiment tend to get heavily ridiculed. I can’t help but find this demoralizing. Why? Because it operates from the premise that code exists to tell computers what to do.

That’s what code is, right?

Imagine you’re the new software engineer at a company. They hired one engineer–you–and the person before you was the engineer who wrote the entire code base. Your job is to make changes to that software to keep the company moving. To most people, your job is to tell computers what to do.

Here’s the problem: the engineer before you didn’t think about somebody having to read or understand the code they wrote–their job was to tell the computer what to do. So they left this gnarled mess that is hopelessly opaque, with code smells so bad they’ll make you vomit. We’ve all seen (and I’m sure we’ve all written) code just like it.

It would be infuriating to find yourself in this position. You have no knowledge of how this thing works, and you’re expected to ship a half-dozen bug fixes by the end of the week. You can go through the troublesome process of changing things to figure out what they are, but trial and error is tedious and time-consuming. You could go line-by-line and figure out what exactly the computer is doing, but that’s a massive pain in the ass. Your ability to do your job is now dampened by the previous engineer’s inability to communicate.

Now imagine that littered throughout are little comments that say things like /* Fixes #10928 */ or // Iterate through the list and updates orders to match batch sizes. Is the code any cleaner, simpler, or maintainable? No, it’s not–the code is still hard to read. All those comments do is either clutter the code base or pass off ugly code as acceptable because a little comment explains what it does.

So what’s the solution to this problem? Is it more comments?

No. No it’s not.

Consider the following example. It’s fizz buzz, but with comments:

/* ... */

// We're going to print fizz and buzz here

for (int i = 1; i <= 100; i++) { // Threshold is 100

if (i % 3 != 0 || i % 3 != 0) { // Print out numbers that are not multiples of three or five

System.out.println(i);

}

if (i % 3 == 0 && i % 5 == 0) { // Divisible by 3 or 5

System.out.println("FizzBuzz");

} else if (i % 3 == 0) { // Divisible by 3

System.out.println("Fizz");

} else if (i % 5 == 0) { // Divisible by 5

System.out.println("Fizz");

}

}

/* ... */

“Hey,” one might say, “those comments are good! They’re telling me what the i % 3 == 0 means, and that’s really helpful!” To someone without much experience with the modulo operator, those comments are helpful. To an experienced programmer, those comments are at best redundant, and at worst clutter.

There’s other ways to communicate that information without a comment. Consider this next example:

private static final int FIZZ_BUZZ_THRESHOLD = 100;

/* ... */

printFizzBuzz();

/* ... */

private void printFizzBuzz() {

for (int numberToTest = 1; numberToTest <= FIZZ_BUZZ_THRESHOLD; numberToTest++) {

boolean divisibleByThree = numberToTest % 3 == 0;

boolean divisibleByFive = numberToTest % 5 == 0;

String message = fizzOrBuzzOrNumber(numberToTest, divisibleByThree, divisibleByFive);

System.out.println(message);

}

}

private String fizzOrBuzzOrNumber(int number, boolean divisibleByThree, boolean divisibleByFive) {

boolean notARelevantMultiple = !divisibleByThree && !divisibleByFive;

if (notARelevantMultiple) {

return Integer.toString(number);

}

String fizzBuzzOrBoth = "";

if (divisibleByThree) {

fizzBuzzOrBoth += "Fizz";

}

if (divisibleByFive) {

fizzBuzzOrBoth += "Buzz";

}

return fizzBuzzOrBoth;

}

I made several changes in this second example that I think illustrates my point: the comments in the first example could be represented as code. Let’s pick them apart:

- I labeled all that logic with a method name. Instead of saying

We're going to print fizz buzz here, it’s in the name of the method–printFizzBuzz. That method does what it says it does. - There was a limit to our fizz buzz loop. There’s probably a reason for that to exist, but just a magic-floating

100isn’t very descriptive. If I needed to change it, I’d have to know that100was the magic number that stopped iteration. Extracting that number out to a separate variable gives context for that number. - Instead of using

i, I used the namenumberToTest. Again, the variable name is descriptive: it’s not just some throwawayi. It’s a number that we need to check, evaluate, and eventually make a decision about. - I extracted two variables:

divisibleByThreeanddivisibleByFive. Those variables say exactly what characteristics aboutnumberToTestwe care about: is it divisible by 3 or by 5? It takes that more alien modulo syntax understandable by the compiler and gives a nice label to it that’s understandable to a person. - I pulled out the decision-making step into a separate method. It’s only 16 lines long and is pretty straightforward. It outlines clearly the case of a number whose value is not a multiple of three or five, and encapsulates the logic around printing “Fizz” or “Buzz” or both. If we needed to adjust that logic, it’s all right there, with pretty labels to read on what everything is doing and why.

- The original method is clean as a whistle–it’s a loop, a couple of variables, a call to a private method, and a print statement. There’s no ambiguity as to what is happening–it’s all right there in easy-to-digest chunks of camel case prose.

What’s the downside to this approach? There’s more code doing the same thing, and… that’s it. That’s the only downside–that it takes up a few more bytes on my hard drive.

If source code file size is an issue, then (1) why are you programming it in Java, and (2) are you sure Java was the right thing to write it in? Maybe we should use a higher-level language, like Ruby, or lower one, like assembly. Or maybe you need different compiler options than what you’re using–flags for those exist, even in Java. The solution to “hey this code is hard to understand” isn’t a comment–it’s more expressive design, built on the bricks of well-selected variable and method names.

I’m hardly the first one to point this out–Uncle Bob explains this well in his book Clean Code. As he says in his book, “Comments do not make up for bad code.”1

The last engineer did not do their job

They told the computer what to do. They did not tell you what the computer is doing. The dogma mentioned earlier is only a fraction of our job–we write code to tell the computer what to do and to tell people what the computer is doing. Code that is understandable but does not work is worthless. Code that works but is not understandable can convince an unknowing manager, but is worthless when it comes time to change it.

When should I use a comment?

A well-placed comment is valuable, particularly when it’s expressing something that code can’t. Perhaps a legal requirement forced one design or algorithm over another. A quick TODO comment to remind you to come back to something before checking your work in could be helpful. In each of these cases, a comment is acceptable when the programmer fails to express something through the code itself.

A comment should never be used to explain what the computer is doing–code exists for that. It usually should not explain the reasons behind a code decision–version control messages exist for that. Great care and forethought must go into writing a comment, always in service of upholding the second part of our job: to explain to a human what the computer is doing.

A comment explaining a gnarly piece of code is just as valuable as spraying a bit of Febreze on your rotting garbage–it’s trying to hide the smell, but trust me: you’re not fooling anyone. Comments do not make up for bad code.

-

Clean Code by Uncle Bob, page 54 ↩