I’ve started reading this book on algorithms and data structures, and I thought it may be wise to explore some of the ideas and practices that the book explores. The first section is on stacks, so I went ahead and implemented the various implementations that the book describes. All of my implementations and experiments are in this repo.1

Stacks

Stacks are an abstract data structure. They can hold virtually anything and follows the pattern of First In Last Out (FILO.) To be a stack, a structure must support at least these three operations:

push(item), which places an item on top of the stackpop(), which removes that item off the stackisEmpty(), which indicates whether or not the stack has anything inside it.

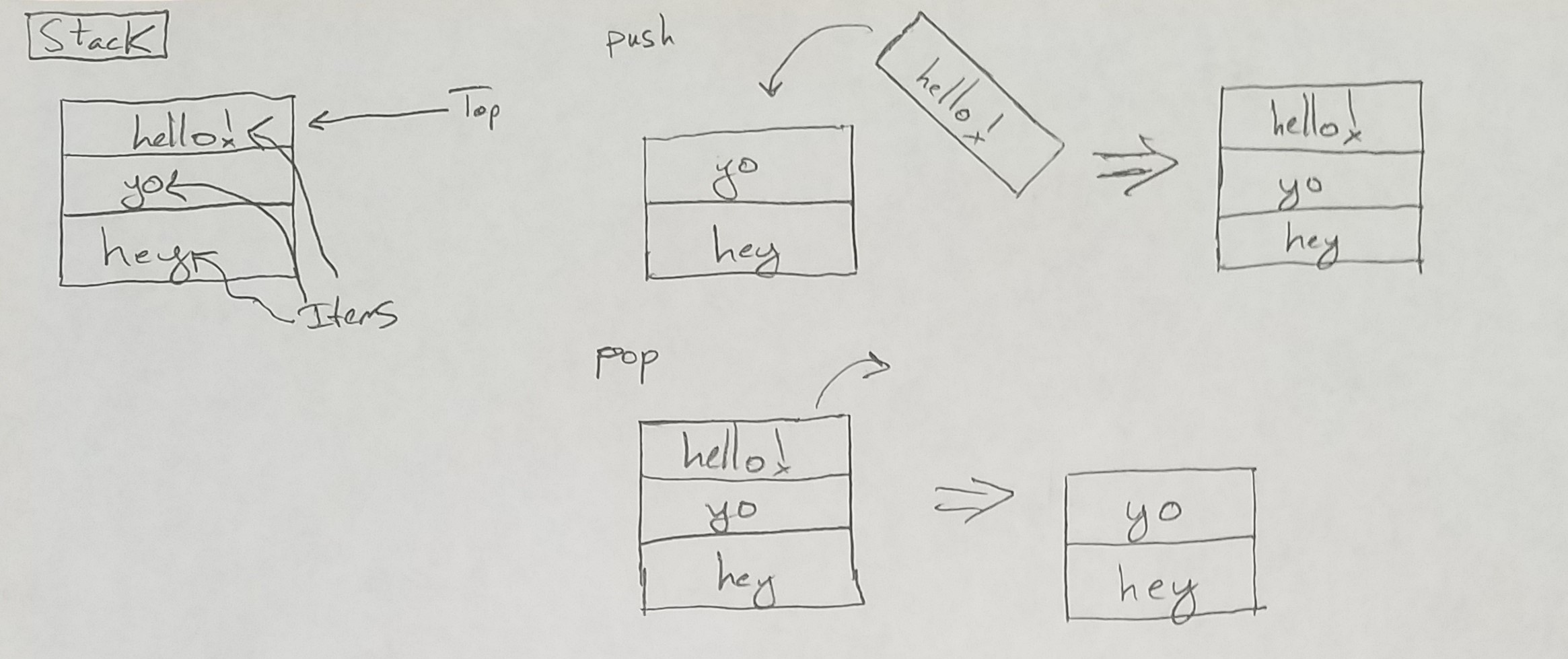

Here is a crude drawing of the abstract representation of a stack:

Different implementations

There are two basic ways to implement a stack: as an array, or as a linked list. They each have pros and cons:

- Array implementation

- Pros

- Fully contiguous in memory makes cache hits more probable

- Straightforward implementation

- Cons

- Limited size (can be sidestepped by making size dynamic)

- Requires allocating memory for space that may never be used

- Pros

- Linked list implementation

- Pros

- Dramatically reduced memory usage

- Does not over-allocate

- Cons

- Distributed in memory makes cache misses more probable

- Linking/unlinking takes more time to do than adding to an array

- Pros

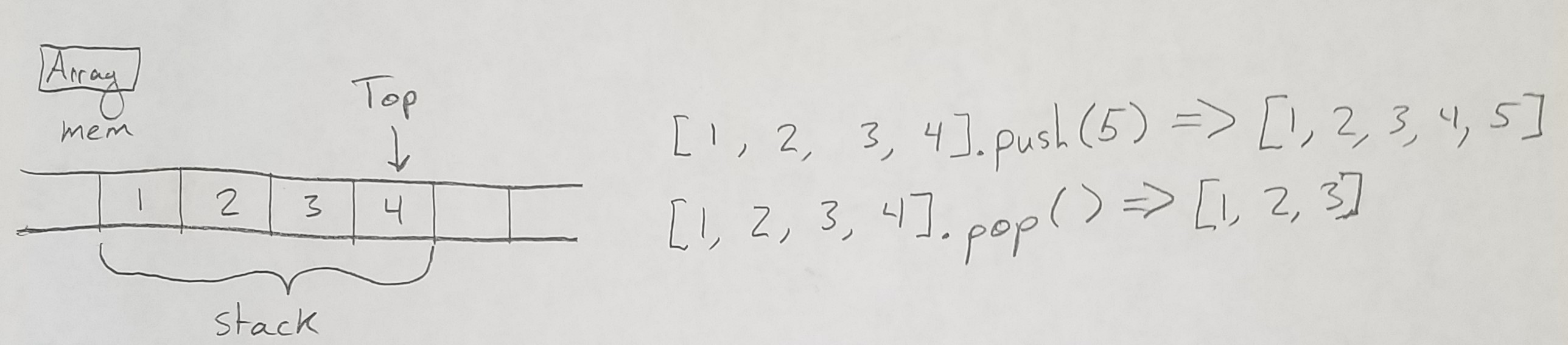

Array Implementation

The array implementation works exactly the way it sounds: it uses an array. An array takes up a contiguous amount of memory, placing each element in each spot. Pushing and popping is as simple as appending or removing an element on the end of the array.

Here’s my implementation. Some pieces to note:

- I set a default starting size for the first constructor, and created a second constructor that allows to set the starting size. I did this to make testing easier and to allow us to explore the ideal starting size of an array stack.

- I implemented the dynamic form of this stack–if we don’t have space on the stack when we need to push something onto it, I double the stack’s size and then put the new item on top. I do not allow reducing the size.

- I included a

peekoperation as well as aclear. This will be useful to us later.

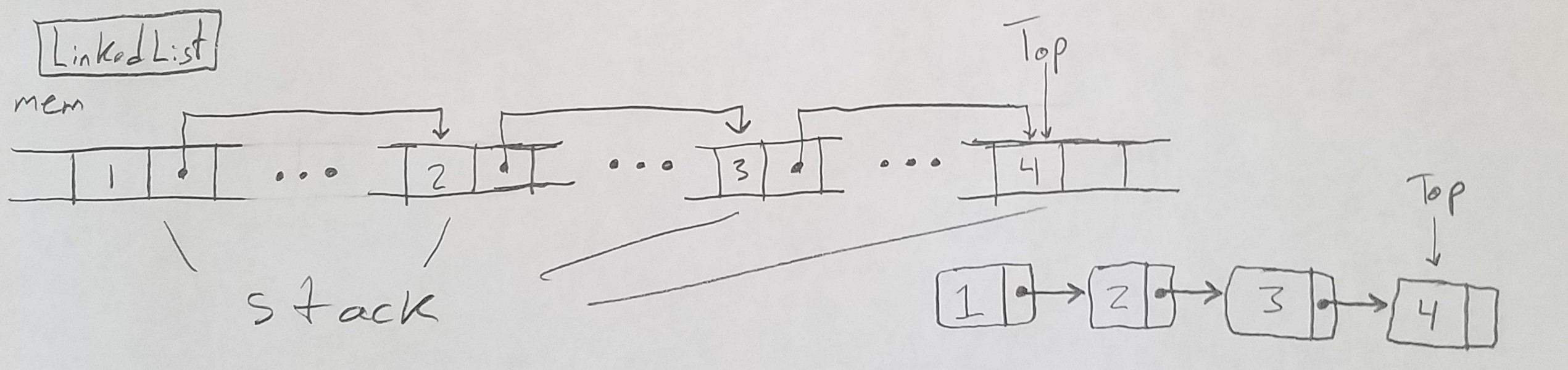

Linked List Implementation

The linked list implementation works by linking non-contiguous pieces of memory together, with each node in the list pointing to the next thing in the list.

Here’s my implementation of the linked stack.

- Notice that I have to keep track of the size on the side. I could have kept this dynamic, iterating through the stack and counting all of the nodes, but that would have made

isEmptyrun onO(n). An extra 32 bits here allows us to keep that. pop()has a check for whether or not we are on the placeholder node. The idea of using a placeholder node came from the book I’m reading, and so I opted to keep it here. This means we never have to worry aboutheadbeingnull; it will always be there.

Comparing Implementations

I wanted to see them in action, and so I wrote a bit of code to evaluate the performance of each of the two implementations. I ran a couple different experiments exploring their performance.

Experiment 1: Nanoseconds per operation

I tested each stack implementation by adding 1000 integers to each of them and timing how long it took to do so. I tested adding 1000 elements, clearing the stack in-between each trial, and I tested adding without clearing the stack between each trial (this means I added 1000 elements to the stack each time.) I made 1000 trials of this experiment and took the mean time for each of them. Here’s my results in nano seconds:

| Stack Type | Clear Between | No Clear Between |

| ArrayStack | 15ns/op |

18ns/op |

| LinkedStack | 19ns/op |

5ns/op |

This experiment shows the clear benefit of an array implementation when the stack can stay relatively small. When the array has to only hang onto 1000 items, the array has to copy itself a few times, but that time is made up by how fast writing to an array is, compared to the linked implementation.

Not clearing between trials does expose the benefit of a linked stack in extremely large quantities of data. When an array implementation has a lot of elements and it needs to grow, it takes a long amount of time to make that change. The linked list implementation has a more constant set of operations for pushing an item onto it: it makes a new node in memory, sets the item, and then links the new node back onto the old top of the stack. When 1000 * 1000 elements are added to a linked list implementation, it never has to stop, allocate a new array, and copy all of the old elements into the new one. This makes the linked implementation the clear winner when handling large amounts of items.

A Blended Implementation

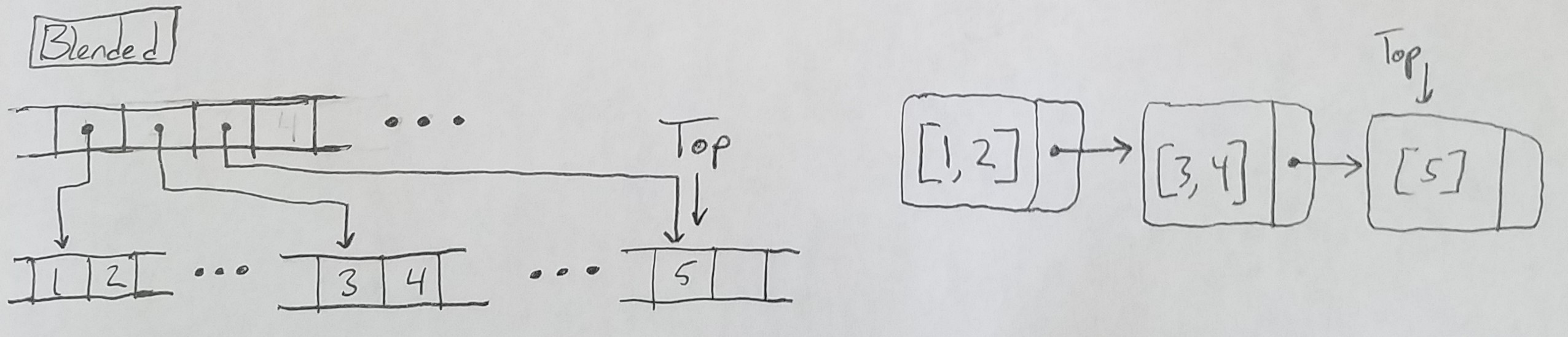

As it turns out, you can blend the two implementations together to get the benefits of both. This blended stack uses a linked list of array stacks as its backing store. You expose the top of the stack by simply exposing the last element of the last array stack in the linked list.

You can see my implementation here.

- I take advantage of my

ArrayStack’s implementation that permits setting the starting size of the array here. Since the array only grows when we need to add something, I ensure an array stack never needs to hold more than this amount. - When the current array stack grows to its maximum size, we simply create a new one and push that onto the linked stack.

I was curious about the ideal array size of a blended stack, so I did an experiment trying to discover the ideal size for adding a bunch of items.

Experiment 2: Ideal array size for adding 1000000 elements

I instantiated a blended stack and timed adding 1000000 elements to it. I did this fifteen times testing against nine different array sizes: 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512. I took the average of the fifteen trials. I got the following results, reported in milliseconds:

| Array Size | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 |

| Time elapsed | 10981ms | 5879ms | 800ms | 502ms | 484ms | 143ms | 222ms | 342ms | 146ms |

The smaller the size of the individual arrays, the longer it took to add an element to it. This makes sense, as a smaller array will make us create more nodes and link them together. When an array stack size is too small, the linked-ness of the blended implementation impacts performance the most. When the size of the array grows, we see the benefits of an array implementation more broadly, up to a point.

This experiment shows that a blended approach can provide the best of both worlds, with 64 as the ideal array size. Given that information, I decided to try my first experiment again, this time including the blended stack.

Experiment 3: Comparing all three implementations

I repeated the experiment in exactly the same way as before, including the blended stack now as another implementation.

| Stack | Clear Between | No Clear Between |

| ArrayStack | 17ns |

21ns |

| LinkedStack | 25ns |

5ns |

| BlendedStack | 15ns |

10ns |

This experiment exposes the real power of a blended stack–it operates roughly the same speed as an array stack (in this case, a bit faster) and holds that performance benefit even when adding large amounts of data. The blended stack isn’t quite as fast as the linked stack for huge amounts of items–its performance is double–but it is dramatically faster than the array stack as the number of elements grows.

Experiment 4: Ideal sizes for each

I performed one last experiment based off of this one to determine what implementation works best for what amount of items. I added 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000, and last 10000000 elements to each stack, figuring out the amount of time to do each. I performed fifteen trials for each size and each implementation, averaging the times. I got the following results:

| Stack | 100 | 1000 | 10000 | 100000 | 1000000 | 10000000 |

| ArrayStack | 148ns |

69ns |

39ns |

15ns |

11ns |

78ns |

| LinkedStack | 277ns |

91ns |

27ns |

5ns |

54ns |

147ns |

| BlendedStack | 339ns |

124ns |

35ns |

9ns |

11ns |

13ns |

The results clearly show that the blended implementation works best when the number of elements is extremely large, reflecting equal performance to the array implementation for 1000000 elements, and dramatically outperforming both implementations for 10000000 elements. This makes the blended implementation the ideal implementation when the stack size is large.

The Verdict

There are three ways to implement a stack: as an array, as a linked list, and as a blended form of the two. Each has its own benefits as each interacts with memory and the CPU cache in different ways. When and why you would use one over the other largely depends on your problem size: more add operations will be more performant with the blended stack over the array or linked stack.

I only explored adding items to a stack here. I’m curious to see how timings compare when it comes to popping items off the stack. That should be the focus of a future set of experiments.

-

I wrote this in Java because I don’t feel like having to deal with memory management in C/C++. Although C/C++ would give a better experience of interacting closely with the machine, I wanted to simply explore the stack structure and call it a day. ↩